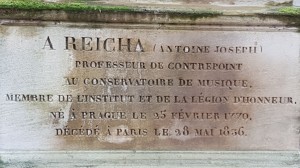

On May 28th 1836, at the cemetery Père-Lachaise in Paris, the now lifeless and musicless body of the Knight of the Legion of Honour and member of the Academy of Fine Arts of the Institute of France was given burial: Antoine Reicha. The following year, a group of colleagues from the Conservatory of Paris defrayed a memorial and had it placed at Reicha’s tomb, so that posterity would preserve the memory of Reicha’s steps on the Earth. A simple plaque reads: To REICHA (Antoine Joseph), professor of counterpoint at the Conservatory of music, member of the Institute and the Legion of Honor. Born in Prague on February 25th, 1770 and deceased on May 28th, 1836. Starting by his name, he was a peculiar character. He was born Antonín Rejcha, then, during his education in Germany, Anton Reicha (pronounced “raixa”) and, later, when he became a French citizen, Antoine Reicha. He shared his birth year with one of the greatest in music: Ludwig van Beethoven. And destiny wanted them both not only to meet, but to become friends. Reicha outlived Beethoven by nine years.

On May 28th 1836, at the cemetery Père-Lachaise in Paris, the now lifeless and musicless body of the Knight of the Legion of Honour and member of the Academy of Fine Arts of the Institute of France was given burial: Antoine Reicha. The following year, a group of colleagues from the Conservatory of Paris defrayed a memorial and had it placed at Reicha’s tomb, so that posterity would preserve the memory of Reicha’s steps on the Earth. A simple plaque reads: To REICHA (Antoine Joseph), professor of counterpoint at the Conservatory of music, member of the Institute and the Legion of Honor. Born in Prague on February 25th, 1770 and deceased on May 28th, 1836. Starting by his name, he was a peculiar character. He was born Antonín Rejcha, then, during his education in Germany, Anton Reicha (pronounced “raixa”) and, later, when he became a French citizen, Antoine Reicha. He shared his birth year with one of the greatest in music: Ludwig van Beethoven. And destiny wanted them both not only to meet, but to become friends. Reicha outlived Beethoven by nine years.

At ten months old, Reicha became a paternal orphan. Apparently, his mother was not very interested in his education and this led Reicha to runaway from home when he was ten years old. His uncle, Josef Rejcha, a virtuoso cellist and composer, adopted the young boy and taught him his first lessons in music. It was Josef’s wife who insisted that Reicha should learn German and French as well. When Reicha was 15, his uncle was appointed cellist and leader of the Hofkapelle, the electoral court orchestra in Bonn. So the couple and the adopted child moved to Bonn in 1785. Soon afterwards Anton Reicha was playing violin and flute (his main instrument) in the Hofkapelle alongside a young violist born in Bonn: Ludwig van Beethoven. In 1789, at age 19, both young musicians joined the University of Bonn. Reicha read mathematics and philosophy. Many years later, in his memoirs of 1824 (Notes sur Antoine Reicha), Reicha stated that algebra and the philosophy of Kant had had a great influence on the way he approached music. In 1794 Reicha left Bonn for Hamburg. In the Hanseatic city, he earned his living by teaching piano, harmony and composition. Then, in 1799, he moved to Paris, where his orchestral works had a good response from the Parisienne audiences. Later, in 1802, Reicha decided to try his luck in Vienna. Interestingly, that year was one of the worst in Beethoven’s life, who had been in Vienna for some years already; 1802 was the year when Beethoven considered the idea of suicide and wrote his famous Heilgenstadt Testament. Reicha renewed his friendship with Beethoven in the Austrian capital, where he spent six years of prolific music writing. He became acquainted with Joseph Haydn, who was then at the peak of his fame.

In 1808, Antoine Reicha decides to settle down in Paris permanently. His reputation as a teacher and a connoisseur of the secrets of German instrumental music preceded him; Reicha was one of the most relevant figures in the European music world, a genuine cosmopolitan artist. In Paris, Reicha was surrounded by a small but very influential group of private students, among them George Onslow and the virtuoso violinist Pierre Baillot. We owe to them that Reicha’s music did not get lost. In 1818, Reicha was appointed professor of counterpoint and fugue a the Conservatory of Paris, where he taught Berlioz, Gounod, Liszt and César Franck among others.

Over a period of 17 years, between 1814 and 1833, Reicha had four major music treatises published. The pianist and composer Carl Czerny translated them from French into German; then English, Italian and Spanish editions followed and Reicha’s reputation consolidated in Europe. In 1829 Reicha was naturalized French and, two years later, he was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour. In 1835, about a year before his death, he was admitted to the music section of the Academy of Fine Arts of the Institute of France.

Having done this short journey through Reicha’s life and achievements, why is it that his music has been in oblivion for so many years? Probably, a great deal of responsibility lies with Reicha himself, because he did not want to have many of his works published. Luckily, there has been a revived interest in the works of this great artist over the last decades. One of the persons we have to thank for the rediscovering and dissemination of Reicha’s piano works –let’s remember his main instrument was the flute– is the pianist Ivan Ilic. To this day, Ivan Ilic has published two volumes with Reicha’s piano works on the British label Chandos. The first volume of the series “Reicha rediscovered”, released in 2017, brings together hitherto unpublished piano works that Reicha wrote after his formative period, around 1800. Among these works, there are three “Practical examples” (Praktische Beispiele), Nos. 4, 7 & 20, which I am going to deal with next.

unpublished piano works that Reicha wrote after his formative period, around 1800. Among these works, there are three “Practical examples” (Praktische Beispiele), Nos. 4, 7 & 20, which I am going to deal with next.

Between 1799 and 1803, Reicha wrote his “Philosophical and practical observations on the musical examples” (Philosophisch-practische Anmerkungen zu den praktischen Beispielen). These Anmerkungen (Observations) are didactical commentaries on the 24 piano compositions of his preceding “Practical Examples, a Contribution to the Intellectual Culture of the Composer” (Praktische Beispiele, ein Beitrag zur Geistes Cultur des Tonsetzers). Reicha explained the innovative character of this work as follows:

I wanted particularly to contribute to the cultivation of the artist’s intellect through the practical examples [Praktische Beispiele] and through the accompanying observations [Anmerkungen] to draw his attention to subjects that could be important for [...] the advancement of his art, just as I wished to see him freed [...] from the slavish bondage in which he has been held by the ignorance and bad taste of most of those who lay down the rules for the use of harmony.

In the Praktische Beispiele, Reicha treats the art of modulation –that is, harmony– in a quite surprising manner. In words of French musicologist Louise Bernard de Raymond, “Reicha constantly goes off at a tangent, suddenly moving to keys or chords that are unexpected syntactically in music of that time”. These “Practical Examples” are very original from the harmonic point of view. They are framed within the aesthetic of the keyboard fantasia, which is very close to improvisation, something very common among musicians of the time: knowing how to improvise was a must. The “Fantasia on a single chord” (Fantaisie sur un seul accord) and Harmony (Harmonie), Nos. 4 & 20 of the Praktische Beispiele, belong to this genre. In No. 4, the harmony is limited to a single chord so that the pianists can feel free to imagine different instrumental figurations. This is how Reicha explains it in the corresponding Observation:

The mind, restricted by a lack of means, seeks (and finds) solutions it would otherwise never have thought of, and thus it attains its goal.

The didactic aim is to give free rein to the imagination of the pianist or composer so that they can improvise and create similar pieces. No. 20, Fantaisie sur un soul accord, has a different character from the fantasia. The work starts with a sequence of sixteen chords, which serves as a pattern for the six fantasias that follow, each of which is based on the harmony of the preceding one and they all have different length, character, metre and tempo (the second one has a quintuple metre, very original for that time). This gives a capricious touch to this piece in line with the improvisation. The rhythmic freedom of “Practical Example no. 4″, Harmonie, where Reicha uses both duple and triple metres, is an example of surprising modulations which defy all the rules: the exposition of this movement in D minor and ends in the very remote key of F sharp major. The “Practical Example no. 7″, Capriccio (Allegro assai), follows a strict pattern of sonata-allegro form, but even so, the spirit of improvisation prevails.

Next time I will be dealing with the other two major works appearing on Ivan Ilic’s first CD dedicated to Reicha: the “Great Sonata in C major” and the “Sonata in F major with variations on a theme of Mozart”. Until then, I hope these words can contribute to arouse the interest of those people who have not listened to Reicha’s works yet.

Michael Thallium

Global & Greatness Coach

Book your coaching here

You can also find me and connect with me on:

Facebook Michael Thallium and Twitter Michael Thallium

Dear Michael,

have you noticed my recordings on Toccata Classics? There are interesting things on all of them but some of the most advanced so far in the series are the pieces in Études ou Exercises, Op.30 and the Frescobaldi Fantaisie (Volume 3) and on the forthcoming Volume 4, to be released on the 6th of March, first of all the two sonatas and the slow beginning of the Fantaisie Op.61.

Yours friendly

Henrik Löwenmark

I’ll check it out! Thanks for your comment!