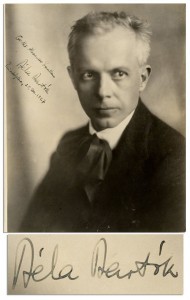

“The sad thing is that I have to leave with so much to say.” – Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

It was the morning of September 26 of 1945. World War II had finished just four months before with a benevolent balance of 50 million people killed. Grape sugar was the only food that had kept him alive at the West Side Hospital in New York in his last week of life: his painful final week. A sudden and sinister drop in Bartók’s temperature five days before had made his doctor persuade him to be taken to hospital. There had been years of hardship for many millions of people, mainly in Europe. He had not been an exception. Like many other people, he had suffered the outrage of a gruesome war and, like many else, he exiled himself to the USA with his second wife, not without first fulfilling his duty as a loving son and looking after his mother Paula: he would not leave Hungary until his mother died in 1940. However, it was not the war that made him depart from this world, but leukaemia. A New York newspaper read:

It was the morning of September 26 of 1945. World War II had finished just four months before with a benevolent balance of 50 million people killed. Grape sugar was the only food that had kept him alive at the West Side Hospital in New York in his last week of life: his painful final week. A sudden and sinister drop in Bartók’s temperature five days before had made his doctor persuade him to be taken to hospital. There had been years of hardship for many millions of people, mainly in Europe. He had not been an exception. Like many other people, he had suffered the outrage of a gruesome war and, like many else, he exiled himself to the USA with his second wife, not without first fulfilling his duty as a loving son and looking after his mother Paula: he would not leave Hungary until his mother died in 1940. However, it was not the war that made him depart from this world, but leukaemia. A New York newspaper read:

“Béla, on Wednesday, Sept. 26, beloved husband of Edith Bartók father of Béla and Peter Bartók. Services at “The Universal Chapel, Lexington Ave., at 52d St. on Friday, Sept. 28, at 2 P.M.”

Béla Bartók, one of the most important composers of modern music, an outstanding specialist in musical folklore and a teacher of wide repute, died on the morning of 26 September 1945 at the age of sixty-four.

It seems impossible for me to accurately sum a person’s life up in just a few lines. Not even a book would be enough just as a mere approximation. No book can truly shape a person’s life, for life is lived individually every minute, every second. The most words can aim at is fixing an idea about someone, an idea whose likelyhood is something we will never be completely sure of. Above all, when you try to remember those great figures in history and their achievements, those achievements we are amazed at. Human beings, we are sometimes so synthetic that we tend to identify a person’s life with a headline, with a bunch of words, thus creating a myth sometimes. Well, those great figures were and are human like the rest of us mortals, with their hidden life experiences, their private experiences and public experiences (the least abundant of them all). I pretty much doubt that Béla Bartók —as self-aware as he was of his worth and his genius as a composer— had ever thought he could go down in history someday and even that someone would include him in the groupd of The Five B’s. In fact, his name is unkown for most people on this planet Earth. Only those who have studied music —Western concert music, to be accurate—, if so, they may have heard of him or played his peculiar Mikrokosmos, that particular world of Bartók for piano learners.

It seems impossible for me to accurately sum a person’s life up in just a few lines. Not even a book would be enough just as a mere approximation. No book can truly shape a person’s life, for life is lived individually every minute, every second. The most words can aim at is fixing an idea about someone, an idea whose likelyhood is something we will never be completely sure of. Above all, when you try to remember those great figures in history and their achievements, those achievements we are amazed at. Human beings, we are sometimes so synthetic that we tend to identify a person’s life with a headline, with a bunch of words, thus creating a myth sometimes. Well, those great figures were and are human like the rest of us mortals, with their hidden life experiences, their private experiences and public experiences (the least abundant of them all). I pretty much doubt that Béla Bartók —as self-aware as he was of his worth and his genius as a composer— had ever thought he could go down in history someday and even that someone would include him in the groupd of The Five B’s. In fact, his name is unkown for most people on this planet Earth. Only those who have studied music —Western concert music, to be accurate—, if so, they may have heard of him or played his peculiar Mikrokosmos, that particular world of Bartók for piano learners.

Bartók, whose music has been criticised as being inhuman by many —I myself have mistakenly thought so sometimes, too—, was a human like the rest of us all. He got married two times. From his first marriage to Márta Ziegler in 1909 —she was 16 years old back then— his first son Béla Bartók junior was born. As a couple, they would undergo World War I, but their marriage would go down the drain as years went by. The summer of 1923 was a time of upheaval for Bartók: his marriage to Márta was irretrievably broken down. In Hungary, divorce was legislated by the 1894 Marriage Act under which two legal faults leading to divorce were stated: one absolute, which included adultery; and another one relative, which included “serious violation of marital duties”. Obviously, it must be pressumed that some fault, absolute or relative, was admitted by Bartók, because the divorce was concluded swiftly. Over that summer of 1923, Bartók had become seriously attracted to one of his piano students, Edith Pásztory (1903-1982). Ditta, as she was generally known, was the daughter of a high school maths and physics teacher and his wife, a piano teacher. Ditta and Béla got married. Márta, despite the traumatic events she was dealing with, continued to working as Bartók’s copyist. Apparently, their marriage had concluded without overt acrimony. After a couple of years, Márta would marry an engineer, Károly Ziegler.

Bartók, whose music has been criticised as being inhuman by many —I myself have mistakenly thought so sometimes, too—, was a human like the rest of us all. He got married two times. From his first marriage to Márta Ziegler in 1909 —she was 16 years old back then— his first son Béla Bartók junior was born. As a couple, they would undergo World War I, but their marriage would go down the drain as years went by. The summer of 1923 was a time of upheaval for Bartók: his marriage to Márta was irretrievably broken down. In Hungary, divorce was legislated by the 1894 Marriage Act under which two legal faults leading to divorce were stated: one absolute, which included adultery; and another one relative, which included “serious violation of marital duties”. Obviously, it must be pressumed that some fault, absolute or relative, was admitted by Bartók, because the divorce was concluded swiftly. Over that summer of 1923, Bartók had become seriously attracted to one of his piano students, Edith Pásztory (1903-1982). Ditta, as she was generally known, was the daughter of a high school maths and physics teacher and his wife, a piano teacher. Ditta and Béla got married. Márta, despite the traumatic events she was dealing with, continued to working as Bartók’s copyist. Apparently, their marriage had concluded without overt acrimony. After a couple of years, Márta would marry an engineer, Károly Ziegler.

Ditta and Béla had a son, Peter. The couple toured internationally performing Bartók’s music. It was Ditta who championed her husband’s music. The same way he had done with his first wife in the early years, Bartók dedicated some of his works to Ditta, in particular, the Piano Concerto no. 3, one of his last works. Bartók wrote this concerto in the final weeks of his life. It was intended as Ditta’s birthday present, but Bartók died before he could finish it, leaving 17 bars without orchestration.

Luckily, there are some testimonies of Bartók’s integrity and fastidiousness. In 1944, being Bartók quite ill and depressed, a famous violinist approached him and asked him to write something for him. Bartók not only wrote something, but he wrote a real masterpiece:

“I knew he was in financial straits, that he was too proud to accept a handout, that he was the greatest of living composers. Unwilling to waste a moment, I asked him the afternoon of our first meeting if I might commission him to compose a work for me. It didn’t have to be anything large-scale, I urged; I was not hoping for a third concerto, just a work for violin alone. Little did I foresee that he would write me one of the masterpieces of all time.”

That famous violinist was no other than Yehudi Menuhin (1916-1999) and the work he is referring to is the Sonata for violin solo.

Who was then Bartók? For some people, he was cold, lacking emotional intelligence, remote, detached, mathematical, unfriendly, pedantic, caustic and humourless; for some others, he was warm, passionate, friendly, caring, engaged, good humoured. How is it possible that the same man elicited these entirely contradictory responses? Well, he was as human as any of us can be. It has even been suggested that Bartók had Asperger syndrome. However, there are some attributes of him that both his detractors and his supporters generally appear to agree about: Bartók was honest, “clean-fingered”, fastidious, egalitarian, industrious and lacking any motivation by material success. His best and lifelong friend, the composer Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) spoke very wisely about Bartók: “even if it is true that these qualities emerged at times, man is not so simple a phenomenon that his eternal secret can be solved by a label with a few lines on it.”

And there is one more thing, as human as Bartók can be, his life’s work can be regarded as simply “superhuman”.

Recomended works by Béla Bartók:

Six String Quartets, 1909-1939.

Concerto for Orchestra, 1943.

Sonata for Solo Violin, 1944.

Piano Concerto no. 3, 1945.Recomended literature:

Béla Bartók, by David Cooper, 2015.

Bartók Remembered, by Malcolm Gillies. Norton, 1991.

Michael Thallium

Global & Greatness Coach

Book your coaching here

You can also find me and connect with me on:

Facebook Michael Thallium and Twitter Michael Thallium

Bellísima semblanza de un grande.Y me guardo para siempre el comentario de Zoltán Kodály …un hombre no es tan sencillo como un fenómeno de modo que su secreto eterno pueda ser resuelto mediante una etiqueta con algunas pocas líneas escritas en ella”.

Gracias Michael!!

Muchas gracias por tu comentario, Cristina.

Bella descripción de un gran ser humano, músico y todo lo que somos en nuestra vida como humanos, gracias por rescatar su humanidad.